The Cost of Kotlin Language Features - Preliminary Results Part 5 - Properties

28 Oct 2017This is Part 5 in a series examining The Cost of Kotlin Language Features in preparation for my presentation at KotlinConf in November. The series consists of

- Lessons Learned Writing Java and Kotlin Microbenchmarks

- Part 1 - Baselines

- Part 2 - Strings

- Part 3 - Invocation

- Part 4 - Nullable Primitives

- Part 5 - Properties

I’m publishing these results ahead of KotlinConf to give an opportunity for peer-review, so please do give me your feedback about the content, experimental method, code and conclusions. If you’re reading this before November 2017 it isn’t too late to save me from making a fool of myself in person, rather than just on the Internet. As ever the current state of the code to run the benchmarks is available for inspection and comment on GitHub.

This post looks at the cost of Kotlin properties. Since my last post I’ve set up a Raspberry Pi booting to Bash to run the benchmarks - the result is a lot less noisy measurements and so better fidelity. John Nolan continues to be the statistical brains behind the Hamkrest matchers used to show the relationships between results.

For the first time these benchmarks use different State objects between Java and Kotlin. In Java we have

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

public class JavaState {

public String field = "hello";

public String getField() {

return field;

}

public String getConstant() {

return "hello";

}

}

so that we can benchmark field access, getter access to that field, and calling a method that returns a constant.

@Benchmark

public String field_access(JavaState state) {

return state.field;

}

@Benchmark

public String getter(JavaState state) {

return state.getField();

}

@Benchmark

public String method_access(JavaState state) {

return state.getConstant();

}

Kotlin doesn’t allow direct access to a field, so the closest State is

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

open class KotlinState {

val fieldProperty = "hello"

val methodProperty get() = "hello"

fun getConstant() = "hello"

}

which we benchmark thus

@Benchmark

fun field_property(state: KotlinState): String {

return state.fieldProperty

}

@Benchmark

fun method_property(state: KotlinState): String {

return state.methodProperty

}

@Benchmark

fun constant_method(state: KotlinState): String {

return state.getConstant()

}

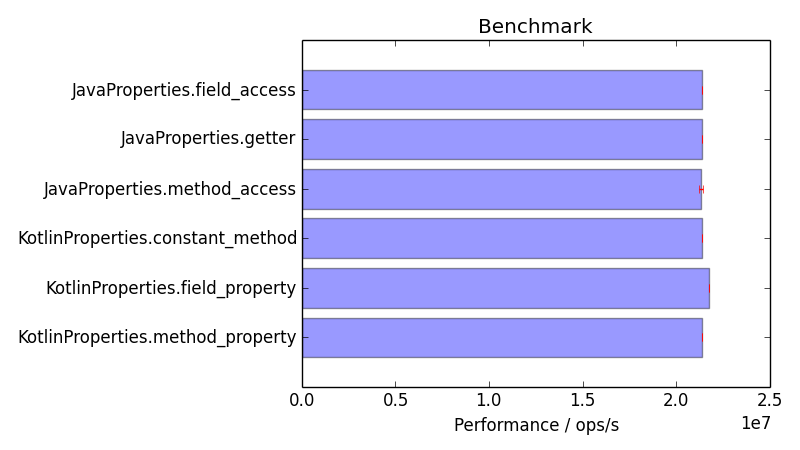

Here are the results for a typical test batch

It looks like everything is the same speed except for field_property. Let’s ask the stats on all the test results that I’ve collected so far.

assertThat(JavaProperties::field_access, ! probablyDifferentTo(JavaProperties::getter))

This first assertion says that we can’t see any statistical difference between accessing the Java field directly, and calling the getter. That’s a surprise to me, as the former is a field access and the latter a method call and the same field access. I suppose that HotSpot has worked its magic (you may recall that we run these benchmarks many times and only start measuring after HotSpot has had time to do so) inlining the getter so that the running code is effectively the same.

The second assertion

assertThat(JavaProperties::method_access,

probablyFasterThan(JavaProperties::field_access, byMoreThan = 0.0002, butNotMoreThan = 0.0005))

shows that calling a method that returns a constant is faster than accessing a field directly. Again that’s a little surprising, but the size of the effect is very small, between 0.02 - 0.05%.

Accessing a Kotlin method property (where we define a get() operation for the property) is unsurprisingly indistinguishable from calling a method, as that is what it is.

assertThat(KotlinProperties::method_property, ! probablyDifferentTo(KotlinProperties::constant_method))

assertThat(KotlinProperties::method_property, ! probablyDifferentTo(JavaProperties::method_access))

That just leaves the outlier - the standard Kotlin property with a backing field. This turns out to be statistically significantly faster than all the other access methods by between 1.5 and 2 %.

assertThat(KotlinProperties::field_property, probablyFasterThan(JavaProperties::field_access, byMoreThan = 0.015, butNotMoreThan = 0.02))

assertThat(KotlinProperties::field_property, probablyFasterThan(JavaProperties::getter, byMoreThan = 0.015, butNotMoreThan = 0.02))

assertThat(KotlinProperties::field_property, probablyFasterThan(JavaProperties::method_access, byMoreThan = 0.015, butNotMoreThan = 0.02))

assertThat(KotlinProperties::field_property, probablyFasterThan(KotlinProperties::method_property, byMoreThan = 0.015, butNotMoreThan = 0.02))

assertThat(KotlinProperties::field_property, probablyFasterThan(KotlinProperties::constant_method, byMoreThan = 0.015, butNotMoreThan = 0.02))

Now I really don’t understand this result. I’ve seen it visually in all the Raspberry Pi test runs and those assertions pass on the amalgam of over 5000 benchmark samples, so it isn’t a statistical aberration, but I can’t see how it can be.

Looking at the bytecode, this:

public final field_property(LcostOfKotlin/properties/KotlinState;)Ljava/lang/String;

@Lorg/openjdk/jmh/annotations/Benchmark;()

@Lorg/jetbrains/annotations/NotNull;() // invisible

@Lorg/jetbrains/annotations/NotNull;() // invisible, parameter 0

L0

ALOAD 1

LDC "state"

INVOKESTATIC kotlin/jvm/internal/Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull (Ljava/lang/Object;Ljava/lang/String;)V

L1

LINENUMBER 9 L1

ALOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL costOfKotlin/properties/KotlinState.getFieldProperty ()Ljava/lang/String;

ARETURN

calling this

public final getFieldProperty()Ljava/lang/String;

@Lorg/jetbrains/annotations/NotNull;() // invisible

L0

LINENUMBER 9 L0

ALOAD 0

GETFIELD costOfKotlin/properties/KotlinState.fieldProperty : Ljava/lang/String;

ARETURN

appears to be reliably executing faster than

public field_access(LcostOfKotlin/properties/JavaState;)Ljava/lang/String;

@Lorg/openjdk/jmh/annotations/Benchmark;()

L0

LINENUMBER 9 L0

ALOAD 1

GETFIELD costOfKotlin/properties/JavaState.field : Ljava/lang/String;

ARETURN

I can believe that HotSpot magic and speculative execution could boost the Kotlin property to the same speed as direct field access, but I don’t see how it can be reliably faster.

Addendum

Luckily the same John Nolan wondered if the final modifiers could be significant. That led me to looking at the field definition, which in Kotlin is

private final Ljava/lang/String; fieldProperty = "hello"

That final probably allows HotSpot to more aggressively inline the value of the variable, safe in the knowledge that no-one can (should) change it. So it’s time to fire up the Raspi and run some more benchmarks to test this hypothesis.

Add-addendum

Well this is even more puzzling! I’ve added final field access Java benchmarks

@Benchmark

public String final_field_access(JavaState state) {

return state.finalField;

}

@Benchmark

public String getter_of_final(JavaState state) {

return state.getFinalField();

}

and a mutable Kotlin property benchmark

@Benchmark

fun mutable_property(state: KotlinState): String {

return state.mutableProperty

}

Against expectations, the Kotlin mutable property seems no slower than the immutable property, and the Java final field access is significantly slower than non-final field access.

We get a clue why the Java final field is slower when we examine the bytecode.

public final_field_access(LcostOfKotlin/properties/JavaState;)Ljava/lang/String;

@Lorg/openjdk/jmh/annotations/Benchmark;()

L0

LINENUMBER 19 L0

ALOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL java/lang/Object.getClass ()Ljava/lang/Class;

POP

LDC "hello"

ARETURN

The value has been inlined, but only after a nugatory(?) call to get the class of the object that it came from. I really don’t understand this at all, but if you do, you could answer this Stack Overflow question.

Add-add-addendum

Well it turns out that the inlining of non-static final primitive and string fields is required by the Java Language Specification, and that getClass call is a cheap null check to make sure that it can’t resolve if the referenced object is null. Given the confusion, and that, for me at least, this is the slower option, I’m not sure that was a good idea.

And I still don’t know why the Kotlin property access is significantly faster than all other options. Let’s hope someone at KotlinConf can put me out of my misery.