The Cost of Kotlin Language Features - Preliminary Results Part 1 - Baselines

07 Oct 2017Following on from my last post Lessons Learned Writing Java and Kotlin Microbenchmarks, this post presents some preliminary results examining The Cost of Kotlin Language Features in preparation for my presentation at KotlinConf in November.

The code behind the investigation is all available on GitHub. There you will find a framework that uses JMH to run benchmarks, and then runs JUnit tests on the results to check assertions about their relative speed. The actual benchmarks and tests that I’m running are also there, along with benchmark results and the sets of those results that are used in the tests. The separation allows me to reject results that are suspect for any of the reasons discussed in my previous post.

Note that, since that post, John Nolan has helped greatly with the statistics of comparing benchmarks and contributed the statistical comparators that the framework uses.

I’m publishing these results ahead of KotlinConf to give an opportunity for peer-review, so please do give me your feedback about the content, experimental method, code and conclusions. If you’re reading this before November 2017 it isn’t too late to save me from making a fool of myself in person, rather than just on the Internet.

With this in mind, let’s dive straight in and look at the baseline tests.

First Java

public class JavaBaseline {

@Benchmark

public void baseline(StringState state, Blackhole blackhole) {

blackhole.consume(state);

}

}

and then Kotlin

open class KotlinBaseline {

@Benchmark

fun baseline(state: StringState, blackhole: Blackhole) {

blackhole.consume(state)

}

@Test

fun `java is quicker but not by much`() {

assertThat(JavaBaseline::baseline, probablyFasterThan(this::baseline, byAFactorOf = 0.005))

assertThat(JavaBaseline::baseline, ! probablyFasterThan(this::baseline, byAFactorOf = 0.01))

}

}

With JMH benchmarks it is important that data used in the benchmark is passed in from the outside world (via State objects), and consumed by the benchmark framework (using the Blackhole)- these limit optimisations that would allow some or all of the benchmark code to be skipped altogether. As pretty much any JMH test requires the use of these devices, I’ve included them in the baseline benchmarks.

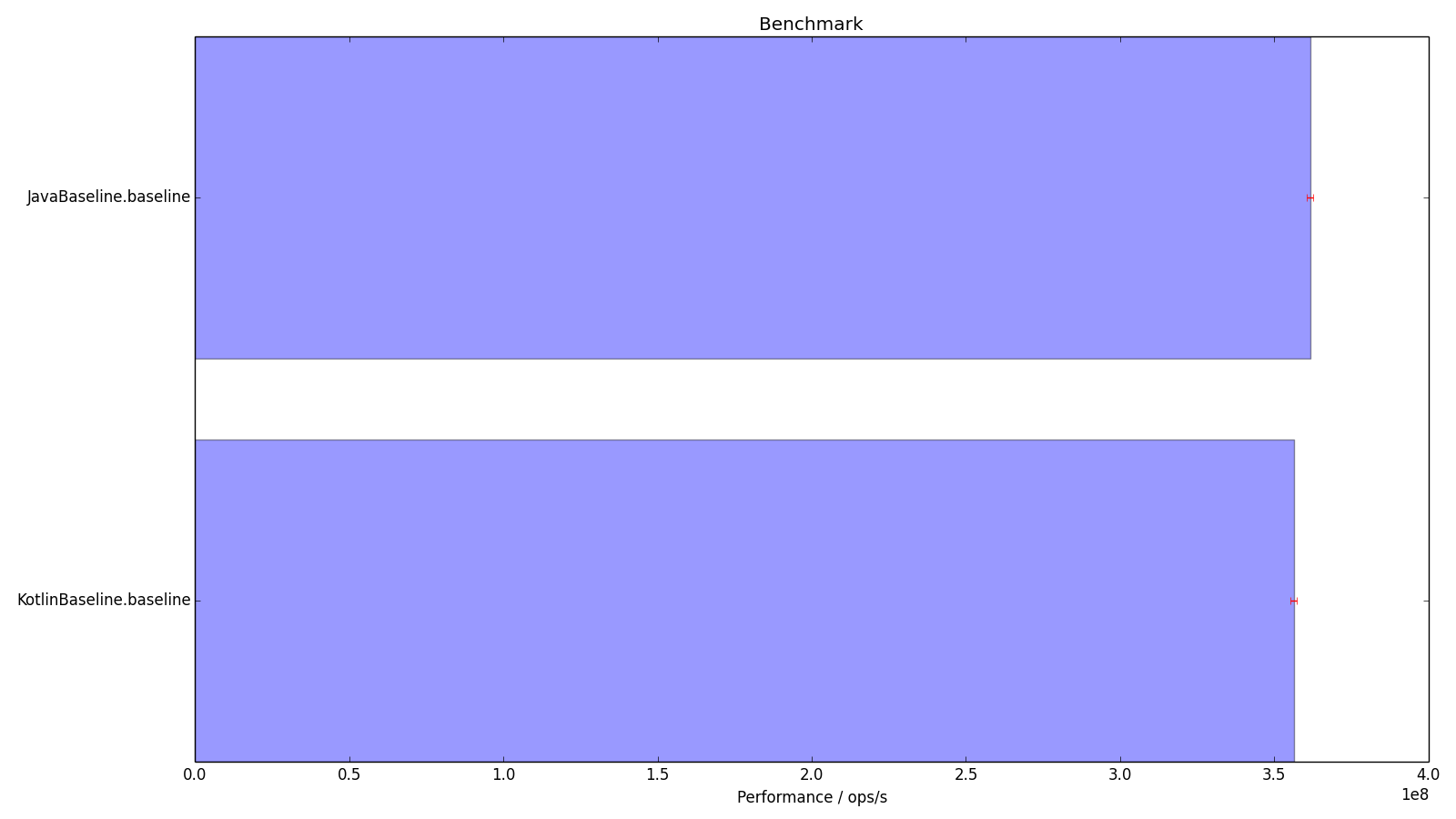

In the @Test we see assertions about the relative performance of the @Benchmark methods. The test shows that the Java code is quicker by between 0.5 % and 1%, with the default Confidence Interval of 95%.

Here is a sample benchmark run shown graphically (the error bars are the mean error with 99.9% confidence).

Given that the Kotlin and Java look functionally identical, you might expect that we shouldn’t be able to detect any difference in the runtime of the code. There is a subtle difference though, revealed when we examine the bytecode emitted by the Java compiler.

public baseline(LcostOfKotlin/strings/StringState;Lorg/openjdk/jmh/infra/Blackhole;)V

@Lorg/openjdk/jmh/annotations/Benchmark;()

L0

LINENUMBER 12 L0

ALOAD 2

ALOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL org/openjdk/jmh/infra/Blackhole.consume (Ljava/lang/Object;)V

L1

LINENUMBER 13 L1

RETURN

compared to that from the Kotlin compiler

public final baseline(LcostOfKotlin/strings/StringState;Lorg/openjdk/jmh/infra/Blackhole;)V

@Lorg/openjdk/jmh/annotations/Benchmark;()

@Lorg/jetbrains/annotations/NotNull;() // invisible, parameter 0

@Lorg/jetbrains/annotations/NotNull;() // invisible, parameter 1

L0

ALOAD 1

LDC "state"

INVOKESTATIC kotlin/jvm/internal/Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull (Ljava/lang/Object;Ljava/lang/String;)V

ALOAD 2

LDC "blackhole"

INVOKESTATIC kotlin/jvm/internal/Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull (Ljava/lang/Object;Ljava/lang/String;)V

L1

LINENUMBER 14 L1

ALOAD 2

ALOAD 1

INVOKEVIRTUAL org/openjdk/jmh/infra/Blackhole.consume (Ljava/lang/Object;)V

L2

LINENUMBER 15 L2

RETURN

The Kotlin compiler always checks that arguments passed to non-nullable parameters are, in fact, not null (at least for public functions). I suppose that in a pure Kotlin world these could be dispensed with, and there is a compiler flag to disable them, but the reasoning goes that any old Java code could be invoking your method with nulls, so it’s better to find this out as early as possible.

This price is paid for invocation of every public Kotlin method, so it’s as well that the check is relatively cheap. In this case you have to run the benchmarks for many iterations before you can see a statistically significant effect.

In the rest of this series I’ll rarely compare Java results directly to Kotlin, but when I do, it’s worth remembering that at least some of any slowdown detected will be due to parameter null checks rather than the rest of the benchmark method.

I hope to have the next installment of this series, covering string interpolation, published in the next few days.

Edit - here are the parts as I write them

- Lessons Learned Writing Java and Kotlin Microbenchmarks

- Part 1 - Baselines

- Part 2 - Strings

- Part 3 - Invocation

- Part 4 - Nullable Primitives

- Part 5 - Properties